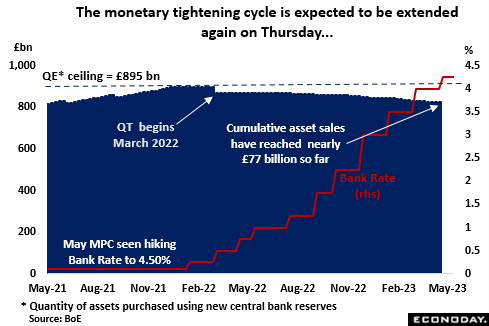

With the central bank committed to getting inflation back on target and the global banking sector looking a good deal more stable, the latest developments in consumer prices suggest that yet another monetary tightening this week is all but nailed on. The widely-held view is that the MPC will choose to hike Bank Rate by a further 25 basis points to 4.50 percent, matching its highest level since April 2008 and making for a twelfth increase in as many MPC meetings. The move would also boost the cumulative tightening in a cycle that began back in December 2021 to some 440 basis points. However, once again the decision is unlikely to be unanimous with MPC’s two main doves (Swati Dhingra and Silvana Tenreyro) seemingly poised to dissent again in favour of no change.

In addition to increasing borrowing costs, the policy stance also continues to be made more restrictive by the QT programme. This has been running, largely uninterrupted, in the background since March 2022. Initially in passive mode but, since late-September 2022 for corporate bonds and the start of November for gilts, incorporating active sales, the plan remains on course to achieve its goal of reducing the bank’s gilt holdings in its Asset Purchase Facility (APF) by £80 billion to £758 billion by November. As of last week, bond holdings stood at £814.4billion. At the same time, the stock of corporate bonds has also been reduced from just over £20 billion to £3.6 billion. These disposals will continue with a view to winding up the programme by around the end of the year. For the quarter just begun, the bank is aiming to sell gilts evenly across short, medium, and long maturities with four auctions in each sector and a planned size of £770mn per auction.

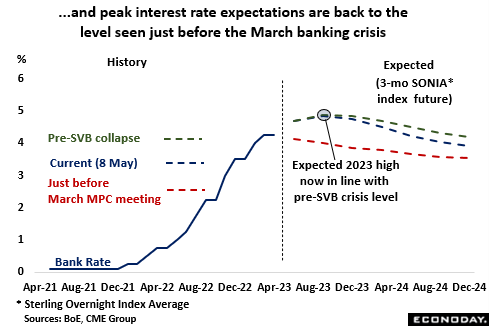

Still, QT has had little impact on market expectations for how high Bank Rate might go. These were cut significantly immediately after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and subsequent run on Credit Suisse but have now climbed again. Indeed, 3-month money rates are now put at 4.85 percent in September, meaning that the impact of the earlier banking sector troubles has been fully unwound. Even so, while investors may remain worried about the near-term outlook for inflation, they remain confident that the BoE will be lowering key rates over much of 2024. By December next year, futures are pricing 3-month money at less than 4 percent and so slightly lower than anticipated just before the start of the banking problems.

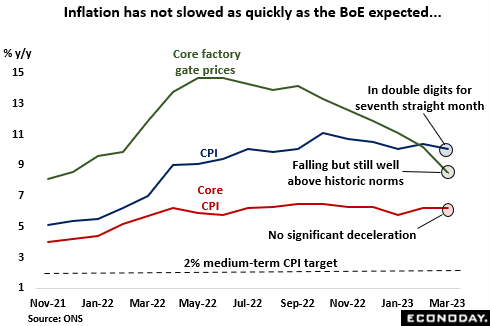

The more aggressive view shown by the front end of the curve in large part reflects the surprising buoyancy of the March inflation data which even the BoE admitted were a good deal stronger than expected. At 10.1 percent, the annual headline rate was at least down from February’s 10.4 percent but, particularly embarrassingly from a policy perspective, in double digits for a seventh successive month and still more than 8 percentage points above target. To make matters worse, the core rate was only unchanged at 6.2 percent, just 0.3 percentage points below the recent high seen in September/October 2022, itself the highest reading recorded in more than 40 years.

To this end, the BoE’s Chief Economist Huw Pill has expressed concerns that what the bank calls “persistent” inflation might be becoming more of an issue. However, by its very nature, this category can be expected to react to policy changes only after a long and uncertain lag so monthly changes in the CPI are of just limited use in determining longer-term trends. Indeed, it might be that a meaningful deceleration here is already in the pipeline, but only time will tell and waiting to find out could raises the risk of policy being kept too loose in the interim. In any event, while conceding that an earlier better understanding of supply chains would have been useful, the MPC has made it very apparent that it wants to see a clear easing in wage pressures before it will feel that it is finally on top of the inflation problem.

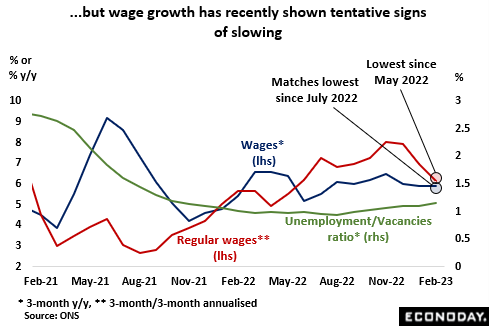

As it is, a quick glance at the latest wage data hardly looks promising. A modest fall in headline annual earnings growth since last November seems to have stalled just below 6 percent, a rate well above anything consistent with the inflation target. However, the bank has indicated that it is also looking at alternative metrics, notably the annualised 3-monthly change and here the signs are more hopeful. Hence, on this basis, from a peak of 8.0 percent in the 3-months to November 2022, the quarterly rate has fallen to 6.1 percent, still far too high but a sizeable decline nonetheless. This will not be wasted on the MPC’s doves. Surveys also suggest that consumer inflation expectations have eased recently but, in line with previous months, in general pay continues to be supported by a tight labour market. Worker shortages remain a real problem for many firms despite signs of some upward creep in the unemployment/vacancies ratio.

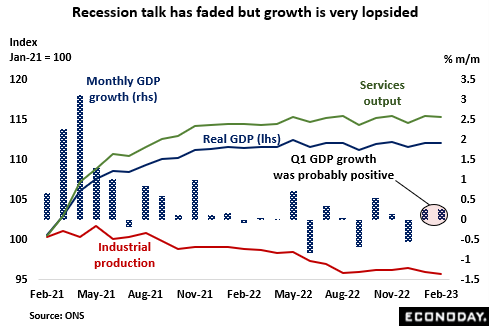

Released at the same time as Thursday’s policy announcement will be a new Monetary Policy Report (MPR). The last edition (February) was much less downbeat on the economy than in December but still saw a contraction in real GDP last quarter (provisional are data due Friday). However, while still possible, growth looks likely to have been positive – absent any revisions, March would need a monthly fall of at least 0.3 percent to yield a quarterly decline. Indeed, but for some 558,000 working days lost through strikes, total output would have been still higher. Nonetheless, the overall economy is lethargic and any upswing very lopsided. Since the start of 2022, industrial production has fallen in eight months and risen in just four, leaving output in February 3.3 percent lower over the period and matching its weakest level since July 2020. Consequently, it has been services, which expanded 0.7 percent over the same period, and construction, up fully 5.8 percent, that have been driving the recovery. However, looking ahead, the ongoing squeeze on real incomes will probably keep consumer spending in check while the impact of rising interest rates on the building industry threatens to offset the benefits now being felt from much-improved supply chains. In sum, the 2023 economic outlook remains sluggish as best.

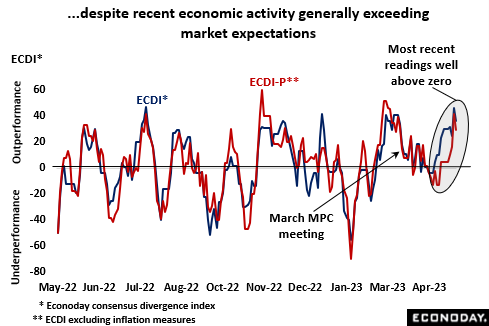

Nonetheless, since the March MPC meeting much of the economic data has surprised on the upside, particularly recently so. In fact, the UK’s ECDI and ECDI-P have been fairly consistently above zero since late February and positive readings on both should bolster the case of those MPC members keen to see interest rates raised again.

In any event, the MPC is struggling to understand the main drivers of inflation. The bank has acknowledged that the linearities of the economic models currently used to build its forecasts leave them ill-equipped to deal with the recent shocks and subsequent heightened volatility in the data caused by Covid and the Russian invasion on Ukraine. Consequently, while March’s 10.1 percent inflation rate probably means that another 25 basis point hike in Bank Rate this week is unavoidable, even an improbable unanimous decision would likely leave few voters totally convinced that the bank is doing the right thing.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings.

Econoday’s Global Economics articles detail the results of each week’s key economic events and offer consensus forecasts for what’s ahead in the coming week. Global Economics is sent via email on Friday Evenings. The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day.

The Daily Global Economic Review is a daily snapshot of economic events and analysis designed to keep you informed with timely and relevant information. Delivered directly to your inbox at 5:30pm ET each market day. Stay ahead in 2026 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.

Stay ahead in 2026 with the Econoday Economic Journal! Packed with a comprehensive calendar of key economic events, expert insights, and daily planning tools, it’s the perfect resource for investors, students, and decision-makers.